- Home

- Sam J. Lundwall

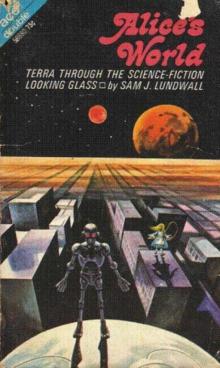

Alice's World Page 4

Alice's World Read online

Page 4

Martha was silent. The girl took a step toward her and smiled suddenly. “I thought that perhaps you would like it,” she said.

Martha asked slowly, “Who are you?”

“Alice.” The smiling eyes held Martha’s, the mischievous childish eyes, with laughter hidden behind the blue irises. “I live here.”

“Here?”

“Well, not exactly here, but not far away…. You didn’t seem happy, but you liked the fairies, didn’t you?”

Martha found herself smiling in response. “Perhaps.”

“What do you want?” the girl asked.

Martha looked down at Alice, painful joyous laughter in her throat. It was so amusing, so incredibly, impossibly amusing. Did she want anything? What was there to want? Didn’t she have everything anyone could wish for? There was beauty around her, peace, love. Only—

“Jocelyn,” she said. “I want Jocelyn.” She still smiled, her face frozen in a painful grimace of forced joy. “But he is dead,” she said.

A comer of her mind screamed at her: Why am I doing this? What is happening to me? Why am I saying this?

Aloud, she repeated, “But he is dead.”

The girl stared at her. “Oh,” she said slowly.

Martha turned back to the grove. She felt dazed, drunken. A warm feeling of happiness and well-being slowly spread through her body, drowning out the small, insistent voice that kept asking Why, why, why. She smiled drowsily and looked down into the glade. It was deserted.

She giggled.

Something moved in the dusk beyond the glade. A tall, shadowed man came into view, his face hidden in the dark. He called softly out to her.

“Martha?”

Her vision blurred as she ran through the grass. “Jocelyn!” she cried. “Jocelyn!” She cried and laughed at the same time.

Behind her, Alice stood, gazing at the grove. Wind rustled and a rabbit jumped up at her, begging for attention. She bent down and fondled it absently. The rabbit whined happily.

Martha reached the glade, embracing, embraced. The glade was filled with light, yet the man’s face was still shadowed. He looked like Jocelyn, but then he didn’t. It was a Jocelyn seen through Martha’s eyes, a strange, idealized, stylized Jocelyn. He had a gash over his right eye. His clothes were torn. His voice was almost that of Jocelyn. Almost, but not quite. It was the voice of a Jocelyn only Martha knew.

“Are you happy?” the warm, disembodied voice asked. “Really?”

She smiled and closed her eyes.

On the other side of the grove, Alice scooped up the rabbit in her arms and ran away into the dim forest, leaving the small, sunlit glade where Martha stood, transfixed by someone who could have been Jocelyn.

8

Monteyiller’s ship fell down from the sky engulfed in a sphere of glowing, iridescent light, followed by the drawn-out roar of a continuous sonic boom. Compressed air hit the ruins with the force of a thousand sledgehammers, toppling them down in clouds of dust.

He handled the ship like a bucking horse, hard, unyielding, ruthlessly. The ship’s brain was disconnected from the landing circuits; his agile fingers danced over the flashing buttons of the maneuver console with dizzying speed, steering, correcting, calculating. His gaze was fixed on the visor screen where the landscape rushed by, made into an indistinct haze by the speed. His eyes glittered, his lips drawn back in an almost painful grimace. Cat, in the chair beside him, closed her eyes and leaned back.

Just like old times again, the mad dash down, the destruction, the happiness in his face. She had seen that expression many times before, too many times before, and she hated it. She let out her breath slowly, pictures flashing by behind her eyelids.

They had been together like that for two years, rambling through the galaxy, seeking new pastures for the Confederation, new riches to be exploited, new planets for an ever-growing population. The old colonies were rediscovered as scoutships descended, engulfed in spheres of iridescent light, roaring above the ancient cities and the ruins of former splendor, with destruction in their wake, the air thundering with sonic booms. The New Empire rising: the sound of progress.

They had been one of the best scout teams at the time: quick, reliable and, above all, surviving. The combination had proven itself: calm, compassionate, cunning Cat, the psychologist, the scholar, the beautiful; and Monteyiller, the fierce tornado of a man, the autocrat, the wonder-boy with the hard eyes and the set mouth and the desperate mind. It had been a good time, on the whole, but when they were promoted in the ranks, they left the scouting and each other without regrets. Two years had been enough and more than enough; they knew each other too well, after spending months at a stretch alone in the scoutship and on desolate, lifeless planets, waiting to be picked up by the returning fleet. Love-making kept them together at times, but that was plain and simple lust, without love, the defense against boredom, loneliness and human needs. Silently, they had hated each other.

Her mouth set as the ship raged over the mountains, the desolate plains, the slumbering forests, the dead cities that turned into flying dust behind them. Morning was coming; the clouds were oceans of fire, billowing up over the sky, reflecting in running waters and fragments of broken glass. There would be birds singing down there, and dark shapes awakening in the fermenting jungles. And somewhere, a man and a woman, and something which had been neither. The remnants of the scout team: alone, frightened, dying. The riddle of the Sphinx: the ages of Man. The closing circle: the absolute, inevitable end. She shuddered as the ship bore down, howling like a dark demon, toward the landing site.

The ruins flowed in the morning light and shimmered like mist, slowly stabilizing into new and unknown shapes, stirring with the life of the ancient fables of Man.

The scarred metal of the landing field heaved and became a landscape of low, rolling hills covered with succulent green grass. The mist descended to the ground and formed fairy-rings, waving over the grass. Peacocks solemnly treaded the grass, and there were starlings, robins and swans, and rabbits and kittens, white with pink noses. The air was filled with the scents of bygone summers, the sounds of worlds lost.

And there was the house, which was as no other house, standing on a low grass-covered hill. Its chimneys were shaped like a hare’s ears and the roof was thatched with fur; and under a tree in front of the house there was a table set out with teapots and cups and plates for the benefit of a hare dressed in a blue suit, and a dormouse and a small man with a large black hat. They were all crowded together at one corner of the table, and no one took any notice of the scoutship as it came thundering down in a wide flaming curve from the sky, burning the grass to cinders, sending the age-old trees spinning in the air: the burning monuments of Man returning.

The ship came to a stop a hundred yards from the curious house, hovering silently two feet over the ground. Monteyiller leaned forward in the chair, studying the visor screen.

“Look at that hallucination!” He scowled. “It’s practically real. No wonder Martha and Jocelyn fell for it.”

“If the hallucinations were so real that the ship couldn’t light from the ground,” Cat said, “they’d be real enough for us too.”

“What’s eating you? You think it is real?”

“It might be.”

“You’re out of your mind. Did you ever see creatures like that?” He grinned at her. “Even if they turn out to be real, that’s all the better. I can handle anything that’s real, be it a bloody hare in a business suit or what-have-you.”

He reached out and flipped a switch, activating the ship’s brain. “I want a sample taken of the ground under the ship,” he said. “Make an analysis of it and report. No thorough examination, just tell me if it’s metal or stone or soil or whatever.” He turned to Cat. “That’ll show you.”

There was silence while the ship scooped up a sample of the ground and made a brief analysis of it, then:

“A very simple analysis,” the ship said, “shows the ground to be of ordin

ary Earth soil, very fertile, with numerous microorganisms. The soil is covered with vegetable growth of the species Graminae, which is commonly known as—”

“It’s enough,” Cat interrupted. She looked at him. “It means grass.”

“Grass?”

“Yes, grass. What did you expect it to be?”

Monteyiller swiveled the chair around and got up, swearing. “This is beautiful!” he said. “The damn ship’s conked out too! Look here—this place was a landing field ten minutes ago. I saw it with my own eyes, so how in hell can it be grass now?”

“But it is.” She smiled.

“It can’t be. You’re going to see for yourself. Let’s get out of here.”

The airlock opened. Outside, the green landscape stretched on to the horizon, unbroken except for magnificent ancient trees and the curious house. Monteyiller made a vile grimace at it.

“Grass!” he said contemptuously.

It was grass. Monteyiller rose from his crouching position outside the ship, a curious expression on his face.

“Well, I’ll be damned,” he muttered. He looked at Cat. “Seems I miscalculated in the ship’s navigation. This isn’t the landing field.” He turned to the robot. “Where are we?”

The robot said, “At the place where the first ship landed. You navigated correctly.”

“I did, eh? So where is the other ship, then?”

The robot pointed. “According to the calculations, there.”

“You’re mad. That’s a house. So you see a ship there, eh?”

“I see a house,” the robot said unconcernedly. “However, according to the calculations, the ship should be there.”

Monteyiller looked at the house. It was unnatural, all right, with the animals sitting at the table, right out of some fairy tale for very small children. And the pastoral scenery where the ruins of the spaceport should have been.

Illusions.

Earth gone mad; dreams turned sour; insecurity; old fear awakening.

Somebody, he thought, is playing a joke on me. He corrected himself: Us. The bastard.

The three at the table eyed him with obvious disapproval. “No room! No room!” they cried out when they saw him approaching. He didn’t pay any attention to them, but sat down in a large armchair at one end of the table, only slightly surprised at finding it substantial and hard to the touch. He leaned forward, putting his elbows on the table, gazing at them. “There is room,” he said.

“Have some wine,” the hare said in an encouraging tone.

Monteyiller looked over the table. There was nothing on it but tea. “I don’t see any wine,” he said.

“There isn’t any,” said the hare.

“So why invite me to wine when there isn’t any?” Monteyiller asked, momentarily confused.

“So why invite yourself to sit down when you aren’t invited?” said the hare. “You and your funny friends.”

Monteyiller’s eyebrows shot up. ‘They don’t sit,” he said.

“They would only dare!” said the hare agitatedly.

“Your hair wants cutting,” said the small man with the big hat. He had been looking at Monteyiller for some time with great curiosity, and this was his first speech.

“He is an imagined creature,” the hare said knowingly. “They always look like that.”

“Unkempt, yes.”

“Very unkempt.”

“And one of his friends has a watch ticking inside his chest. I don’t think it is very civil, to come uninvited to tea with a watch ticking inside one’s chest.”

“It’s the same with all imagined creatures; they have no manners at all,” said the hare, looking disapprovingly at the robot.

“The dormouse is sleeping again,” said the man with the hat, and he poured a little hot tea on its nose.

The dormouse shook its head impatiently, and said, without opening its eyes, “Of course, of course; just what I was going to remark myself.”

“Why is a raven like a writing desk?” the man with the hat asked, looking sharply at Monteyiller.

“It was the best butter,” the hare muttered uneasily.

“Once upon a time there were three little sisters,” the dormouse began in a great hurry, “and their names were—”

“Some tea, perhaps?” the man with the hat asked politely.

“…perhaps some crumbs got into the watch as well,” the hare said meekly. “…ticking inside his chest.”

“What day is it? My watch has stopped again.”

“…shouldn’t have put it in with the bread knife…”

They began to speak agitatedly to each other, forgetting the visitors in their argumenting for and against. Monteyiller looked from one to another, wondering if he was sane. Finally, as the discussion went on and no one took any interest in him, he rose from the chair and walked back to Cat and the robot, who had stopped some way from the table, looking silently at the strange scene.

“Don’t ask me,” he said wearily, “because I haven’t the foggiest idea.”

Cat said, “Didn’t you recognize it?”

Monteyiller stared at her. “Me? Why?”

“It’s the Mad Tea Party, from an ancient story. I read it once: Alice in Wonderland.”

“It’s mad, all right,” Monteyiller muttered. “So what?”

She looked past him, pursing her lips. “It could be robots.”

“Sure, robots.” He didn’t sound convinced.

She walked by him, up to the table where the three beings steadfastly refused to take any notice of her. They were dissecting a large pocket watch, the innards of which was partially filled with rich golden butter, lavishly sprinkled with breadcrumbs.

“I told you butter wouldn’t suit the works!” said the man with the hat, looking angrily at the hare.

“It was the best butter,” the hare replied meekly.

“They’re like the robots in the amusement parks,” Cat said doubtfully, looking at them. She turned to Monteyiller. “We might have landed right in the middle of some kind of amusement park; that would account for all this.”

“A damn queer sense of humor they must have had,” Monteyiller muttered, “with that bloody Sphinx tearing people to pieces.”

“They’ve been here for fifty thousand years,” Cat said. “Machines break down sooner or later.”

“You’re a genius,” Monteyiller said sarcastically. He walked past her, toward the house. “Don’t forget to tell me if you get any more bright ideas, will you? And start moving, there’s people here somewhere, needing help. Let’s go.”

Cat came after him. “You think the ship is there?” she asked incredulously.

“How should I know? It just might be, that’s all.”

She sighed, but didn’t say anything.

They entered the house. There was magnificent disorder: shoes placed on the hat-racks, tables turned upside-down and teacups balancing on the legs, bird cages with strange animals which definitely were not birds. The place was quiet and peaceful, and so absurd that Cat couldn’t help smiling.

“Look, Mon,” she began, “isn’t it—”

She was cut off by the door behind them slamming shut in the face of the approaching robot. She whirled around, and gasped.

The air began to shimmer around them, mist poured out from the walls, momentarily obscuring them from view. There was the feeling of space opening all around, and a damp chill coming from all directions. The sounds from the green landscape were replaced by an ominous silence, punctuated by a steady dropping in the distance. Monteyiller was groping forward in the whirling mist, swearing profusely and calling out her name; his boots rang out on hard unyielding stone.

Suddenly, the mist cleared and disappeared. They were standing in an immense stalactite cave, softly lit by some unknown source, scintillating pillars rising up toward the dark roof somewhere high, high above. Cat staggered backward and came upon the stone wall. It was hard and moist to the touch. Monteyiller stood crouched, gun in his hand,

staring at an object in the center of the cave.

There, encircled by iridescent pillars, sparkling with the light of rubies and emeralds and chrysolites, a black scout-ship hovered unmovingly two feet over the ground. Its weapons were retracted into the hull, the airlock was closed. It just hung there, Jocelyn’s and Martha’s invincible, magnificent, trapped ship.

9

Monteyiller leaned back in the maneuver chair, a pained expression on his face. He banged his fist in the armrest, spread out the fingers and stared at them as if seeking consolation in the throbbing pain.

“So it’s the real ship, all right,” he said slowly, “and untouched, too. But as to that bloody cave…” He looked up at the curved screen facing him. It showed the interior of the enormous cave, bathed in the strange pale, light that seemed to come from all directions; but the picture wavered and rippled as if it weren’t quite sure that the cave really was there. Occasionally, a green, rolling landscape could be seen through the rock walls, brief snatches of trees and grass that came and went, exploded into view and reluctantly faded away. Without the aid of the visor screen, the rock was as impenetrable as before, and the ship’s brain stubbornly maintained that the cavern was there, completely and irrevocably. Whatever it was that had created the illusion, it had done its job well. Only the cameras weren’t completely fooled.

“This is it,” he said tightly, staring at the flickering screen. “Trapped in a hallucination, and no way out.” He swiveled the chair around until he faced Cat, in the other maneuver chair. “Any ideas?”

She said, “We could blast our way out. There are disrupters in the ship, and—”

“And get the whole damn roof down on our heads? No thanks!” He raised his hand when she opened her mouth to protest. “Sure, I know it’s only a hallucination, but if we started to blast away with the disrupters, you can bet your sweet neck the roof would come down anyway, hallucination or not. I won’t take any risks.” He swung back toward the screen, his mouth hardening into a thin bloodless line.

Alice's World

Alice's World