- Home

- Sam J. Lundwall

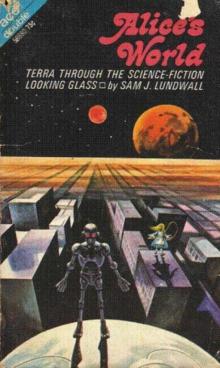

Alice's World

Alice's World Read online

Table of Contents

Alice’s World

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

Alice’s World

Sam J. Lundwall

Author

Sam J. Lundwall is probably the leading science fiction expert in Sweden. For many years one of that country’s most active fans, he has long graduated to professional status. Book collector, critic, writer, and now a novelist as well, he was for several years connected with Radio Sweden as a director of television productions and news programs.

Currently he is the editor of a Swedish language science fiction magazine and a series of science fiction novels for a book firm there. His book about science fiction—a literary and historical account for the general public—has already gone into several printings and is now being translated into English. In addition to all these literary talents, Mr. Lundwall is also a quite well known recorded folk singer and song writer.

1

Already in the early morning, the white stallion had walked the winding path up to the ridge of the mountain. It was a hot day, but he stood there, unmoving, because he had the vague notion that this was expected of him. Beneath him, the ground steamed in the heat, and the creatures down there moved uneasily while they waited for him to give the long-awaited sign; but not until the evening did the event happen that the old women had prophesied. Suddenly the spaceships hung in the sky, like a swarm of flies. They hovered as drops of molten metal in the blue evening light.

Forced by his terrible longing, the stallion strained his muscles and hurled himself out in the air. The mighty white wings spread out from his shoulders and lifted him without visible effort up toward the darkening sky. He swept majestically around the mountain, followed by a thousand watching eyes, and soared with powerful wingbeats out over the endless steel-blue sea, toward the spaceships that danced in the hot evening light far away. Behind him a cloud of flying creatures rose in the air, driven by the same compelling yearning that drove him.

There came the Valkyries on their flying horses, the Phoenix, the Sphinx; a colossal man who came from a distant place called Thrudvang and traveled in a flying chariot drawn by two male goats; thousands and thousands of creatures who rushed forward high above the earth.

Above them all, Medea raged in a golden coach drawn by dragons, with Oistros as coachman; and following the big swarm came a largish beetle who had relinquished the evening star Venus Mechanitis to its fate.

The beetle’s name was Khepre, and its nature was the same as the other creatures. But ahead of them all, the Pegasus soared over the sea, toward the sinking ships. The white mane flowed in the wind, and the air thundered with beats from the mighty wings. The Pegasus soared high above the sea that once was called the Mediterranean, toward the distant islands where the returning men’s ships would land.

2

The first ship plummeted down from the billowing sky in a wide curve, over the mountaintops and the dark forests, and sank down to the ground. It descended in wide circles, silent as a drifting feather. The long iridescent wings that gave the ship an appearance of a dragonfly drenched with light and spread a strange shimmer over the ground. The ship glided down between two crumbling pylons of a metal that once had been blinding white but now was dark and lusterless and covered with fissures where dark green vegetation patiently ate its way in; did a turn over a metal launching platform, rusted and fractured by ancient trees, and landed noiselessly. The slender craft, an unlimited expanse of unbroken black metal, hovered unmovingly one foot over the ground, suspiciously watched by the ships above. The pulsating force-fields that had spread out like wings from the black body of the ship faded away and disappeared.

It was a fine evening, cool and quiet and very, very peaceful.

Inside the ship there were two men fiddling with controls. There were sounds of heavy machinery and the smell of metal and clear oil. A woman dressed in flowing blue stood by the airlock, which opened with a soft soughing sound. She turned around.

“Well?” she asked.

“Well, nothing.” The man had a hard mouth and vacant eyes. “It’s dead. So what do you expect? A welcoming committee?” His voice was high-pitched, contrasting strangely with his burly body.

“It’s so…different from what I expected,” she said, looking out in the dusk. She clasped and unclasped her hands on her back; her hair spilled down black; there was a vague scent of Styrax calamitus.

“You know, Jocelyn,” she said, “just—something.”

“Sure.” The high-pitched voice said.

The ether man, seated in the maneuver chair by the shimmering visor screen, didn’t say anything. He leaned back, hands loose in his lap, eyes closed, a smile on his mouth. His skin, in the wavering light from the screen, had an odd quality. Jocelyn rose slowly from his chair. “Let’s go,” he said.

Outside: It once had been one of Earth’s biggest spaceports—but that was fifty thousand years ago. Now it was a wilderness of moldering structures, where mighty trees triumphantly rose from the uneven ground. Remnants of machines and vehicles lay scattered everywhere. A feeling of decay hung over the place, so thick one could almost smell it. Far away in the dusk one could vaguely make out the crumbling remnants of something that might have been an ancient spaceship. It was incredibly large, the naked beams protruded from the hull like the ribs of a giant, blackened corpse.

Jocelyn and Martha appeared in the airlock, momentarily outlined against the blue-white light in the ship, before they jumped down. The ground was weathered and brittle and crunched beneath their weight. As they walked away from the ship, openings appeared in the hull, and rods and barrels slid out, locking into position with soft, well-oiled clicks. The gleaming metal, humming with power, scanned the surroundings with precise, mechanical movements. There was beauty in the movements, and death.

Martha looked up. She threw out her arms, her eyes widening.

“Look!” she whispered. “Look!”

The landscape changed. The moldering structures flowed and shimmered, growing, transforming. Ruins rose up toward the sky, changing, hardening into stone and crystal; pillars appeared, their surfaces rippling with liquid fire, reaching up and up toward immense arches of petrified light, ringing with the sound of distant bells. The air hardened into emeralds and rubies, sparkling with light, adorning the majestic walls. The ground changed and became an immense stone-paved floor, reaching away into a misty distance; dark massive structures rose, towering above them; the moon changed, splitting into a thousand flickering candles burning beneath the great arches; there was the sound of an immense choir, whispering clearly and singing. Enormous arched windows appeared, the stained glass alive with dazzling light; there were ornaments and sculptures, and impossibly high up in the blue distance of the arches, there were figures moving. It was the cathedral of Rheims, but a hundred times, a thousand times. It rose on and on, never ending, the altar shrouded in billowing mists, the walls burning with the colors of crystals. The ship was a speck of dust resting in the nave between glowing pillars reaching up into eternity. There was the sound of a chime and someone stood in the pulpit, turning the pages of an immense book decorated with strange signs. The voice boomed out, echoing between walls and pillars and ogival arches, carried on the shoulders of the whispering choir, filling the immense expanse of the cathedral.

Jo

celyn threw his hands before his eyes and screamed; and by the terrible fear of the cry the immense voice faltered, the choir became silent. The high-pitched scream filled the cathedral, shaking it. The pillars trembled, the arched windows lost their color, the sculptures melted away. Crystal fell, disintegrating into flashing fragments; the ground heaved, the walls flowed back, shrinking and disappearing in thin wisps of glittering air.

The cathedral collapsed silently, turning into smoke and air. After a moment, nothing was left except for a distant echo of chimes, slowly dying out in the wind.

3

The man in the ship focused his eyes on the screen before him. The ruins returned, brooding in the pale light of the moon, and in a dark doorway, flanked by crumbling pillars of dark green stone, stood a small girl. She could have been about ten years old, in a bright blue dress, white stockings and a newly-starched pinafore. Her hair was yellow and long, falling down her back; she was bouncing a gaily colored ball up and down on the rubble-strewn ground, looking at the ship with mischievously glinting eyes and shaking with suppressed laughter.

The man regarded the screen with cold, impassive eyes for a while, then abruptly disconnected the camera and swiveled the chair around. He looked thoughtfully at the dials, still registering the unbelievable mass that had surrounded the ship, coming from nowhere and departing again. Had he been anyone else, he would have whistled; but of course, he wasn’t. In the merciless blue light of the meter console, the smooth flesh-colored oval of his face was clearly revealed, featureless except for the large unblinking eyes and the delicate round mouth. It was an orthodox arrangement, to be sure, but, then, people prefer their robots as human as possible. He threw a couple of switches and connected unhurriedly with the flagship, hovering somewhere above. A mirage, probably, or a hallucination. He leaned back in the chair as the image of a uniformed man slowly appeared on the screen. There was nothing unusual in hallucinations. But on the other hand, even if human beings can experience hallucinations, robots never do.

“But he did!” Monteyiller said. He was a big, stout man dressed in a simple blue tunic with the spaceship-and-sun sign embroidered on the left breast. His eyes, under the mass of unruly black hair, were narrowed, his nose large and aquiline, the mouth determined. He leaned over the table, passing his eyes over the people in the room. “He saw it,” he said, “and the instruments bear him out.” He hesitated. “Some of them, anyway. Now, what kind of hallucination would do that, I ask you?”

Edy Burr, one of the computer specialists, looked up. He said, “You want my professional opinion?”

“Well, of course.”

“In that case, I haven’t got any. I handle the computers, they’re good things, mostly, logical and all that. I fed in the information about this…occurrence….” His voice trailed off.

“Yes?”

“As far as the computers are concerned,” Edy said, “it was a hallucination. I got some very good proof, too.”

“I wish I had your simple faith in your computers,” Monteyiller said. “Unfortunately, I don’t.”

“Hallucinations can happen,” said Catherine diRazt, the psychologist. “Especially under stress. Jocelyn and Martha were quite wound up, weren’t they?”

“Sure.” He smiled joylessly at her. “And the robot as well, perhaps? And the instruments?” He straightened up and went around the table, to the visor screen that covered one of the walls of the room. “And the television system as well, I gather!” He shook his head. “What kind of hallucinations can be seen on a visor screen, I ask you.”

“Mirages…” Edy said, uncertainly.

“Mirages, my ass! The mass meters nearly jumped off their pins when that…thing appeared. Just appeared out of nothing and then disappeared again. Now, what kind of hallucination is that?”

“A cathedral,” someone said, “early Gothic, I would guess. Very impressive architecture.”

“Thanks,” Monteyiller snapped, “for nothing. Look, I don’t care if it was a fairy castle standing upside-down. I want to know where it came from and how; that’s all I’m interested in. And don’t tell me what the computers say, because I don’t care about that either. Any ideas?”

None. Monteyiller raised his eyebrows, shrugged and turned to the visor screen. Pictures blazed forth there, pictures of heavily surging waters, forests, jungles, endless savannahs where half-sentient creatures roamed beneath the scorching sun, snow-covered wastes, mountains, valleys, deserts, seas. And ruins. From the fourteen dragonfly-ships that circled the planet, telescopic cameras tirelessly watched the landscape and transmitted a never-ending stream of pictures to the ships. The pictures alternated continuously, but the result was the same.

At the poles, the ice had swallowed the cities and strange white beasts patrolled the wastes where once the spires and pylons of an incredible civilization had soared toward the limitless sky. The jungles had covered cities and spaceports with an impenetrable covering of fermenting verdure; the glittering spires had fallen beneath the ancient giant tree’s roots; and in the former parade halls the apes presided in a pitiable parody of the Imperial rulers’ pompous court. On the beaches, on the plains and in the mountains, the cities lay wrecked and crumbled down to dust. Everything was dilapidated, forgotten and defiled. A thousand years from now, nothing would be left of Man’s achievements. It was a pitiable sight, but not wholly unexpected.

“I wonder what we had been expecting,” he muttered looking at the screen. “A developed civilization, perhaps…the old Empire still going strong and giving the big welcome to the lost son.…It doesn’t exactly look promising.” He frowned, and turned around. “Okay,” he said, “that’s all. Try to come up with something, anything at all. But make it fast.”

The room emptied amid a murmur of dissenting voices, abruptly cut off by the closing door. Monteyiller gazed vacantly after them, lost in his own thoughts. He felt old and tired, the skin on his face was dry and rough, and weariness washed over him like waves on a slowly surging sea.

Someone moved in the room. He looked up and met the eyes of Catherine diRazt, standing by the table. “So you’re staying, Cat? Just like old times, isn’t it?” He smiled. “Always the good Samaritan, giving consolation to anyone in need. Or perhaps you have some ideas?”

“You know I haven’t.”

“Consolation, then.” He leaned back, clasping his hands behind his head. “You know, for a moment I thought you had something else. Any good, uncomplicated explanation would do.” He looked thoughtfully at her. “You think it was a hallucination?”

“No.”

“Neither do I. And, you know, it scared the living hell out of me. What’s going on here?”

She sat up on the table, tucking her legs under her in the familiar way he knew so well. There was a world of memories in her movements, the hint of unspoken words, the volumes of questions and answers in a raised eyebrow, an inclined head, a closed mouth, a quick gesture with a hand. The lithe body beneath the blue tunic, bearer of no secrets, the long graceful hands that had caressed him so many times. Yes, him. He looked up into her eyes.

She’s pitying me! he thought. It’s all the same, pitying, and the kind words and the kind deeds, damnit! That’s the perfect psychologist for you, but she was born that way, with a confessional in her head. The compassionate, passionate.

Suddenly, he longed for her.

Years back: They had been a good, reliable scout team, thrown together by a computer’s whim and sent out to months of togetherness. Two months in a ten-by-ten foot cabin makes lovers even of strangers. Bodies joining in hate, if not in love. Fighting boredom with lust: and they had managed. They had managed.

They had preceded the fleets of the growing Confederation of Planets, riding the currents of space in their diminutive scoutship, homing in on the dead planets of the dead Empire where ancient splendor lay moldering under alien suns, the sepulchers of Man, scattered over the eternity of space. There had been dead cities, dead memories, dead glory, b

lank-eyed savages cowing before still blazing visor screens amid the rubble of palaces and iridescent buildings. They had landed on Petara, Karsten, Chandra: beautiful, ancient names, once famous. Sometimes, there had been disembodied subspace voices guiding them in, giving detailed instructions, allotting them landing space in immense spaceports where thousands of gigantic starships rotted. The police voices had been those of computers and still functioning robots, performing their last duties for a forgotten Empire. The vibrations from the landing scoutship caused buildings to totter and fall, burying the machinery beneath tons of smoking plastic and steel. The Empire had built well, but not for eternity. As the Confederation spread out, the old Empire died quietly.

And now Earth, the center of it all. After that: nothing.

“You look tired,” she said, leaning over him.

“I am. Forty hours without sleep usually makes me tired.” He sighed. “Too much depends on this thing. I simply can’t afford to let something happen while I’m snoring my head off. You haven’t the faintest idea of how much the Confederation has sunk into this expedition… You know, back to the old Empire center, glorious deeds, a whole treasure chest of a planet, everything waiting for us to pick up, and Thorein knows we need everything we can get….” He relaxed, smiling at her. “And now the whole bloody thing is starting to blow up in my face.”

It was damn easier to be a scout, he thought. I wonder what it would be like, to do it again. To go out again, to the months in the ship, to the weeks on the planets. To be years ago again. And Cat again, for what it was worth.

She said quietly, “You’ve changed, Mon.”

“Everybody’s changed. You. Me. Everybody. So what’s strange about that? We have to grow up sometime, don’t we?”

“You were different then,” she said. “Softer. You’re getting cynical.”

“Power,” he said, “corrupts. You should see my soul, blackened by guilt. Sometimes I hate myself, but only sometimes. As for you…” He became silent.

Alice's World

Alice's World